The History of Sleep Aids: From Ancient Herbal Remedies to Modern Precision Medicines

Thompson Le

Medical Affairs Intern

Humans have struggled with sleeplessness for thousands of years, long before we understood the biology of sleep. What has changed is how we approach insomnia, from experimenting with natural sedatives to developing targeted therapies based on neuroscience. The evolution of sleep aids reflects advances in chemistry, pharmacology, and patient safety.

Ancient Roots: Early Attempts to Induce Sleep

Long before modern medicine, cultures around the world used natural remedies to treat insomnia. Egyptians used opium-rich poppy extracts for sedation; Traditional Chinese Medicine relied on herbs like suan zao ren and valerian root, now known to influence GABAergic pathways. Greek and Roman healers mixed wine with plant alkaloids to promote sleep, while medieval Europeans used mandrake and belladonna, plants capable of sedation but also hallucinations and toxicity. These early treatments showed that sleep was recognized as vital, but pharmacologic attempts to induce it were often unpredictable and dangerous.

Poppy seeds. Center for Science in the Public Interest. Published September 11, 2024. https://www.cspi.org/poppy

Lustrea J. Valerian – Mother’s Little Helper During the Civil War. National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Published August 18, 2021. https://www.civilwarmed.org/valerian/

1800s–Early 1900s: The First Synthetic Sleep Medicines

The invention of chloral hydrate in 1869 marked the first major step toward modern sedatives. It provided more predictable sleep, though we now know it works by converting to trichloroethanol, a GABAergic compound. Bromide salts soon followed as sedatives and anxiolytics, but long-term use caused “bromism,” a toxic neurologic syndrome. These drugs were an improvement over herbal mixtures, yet their toxicity highlighted the need for safer options.

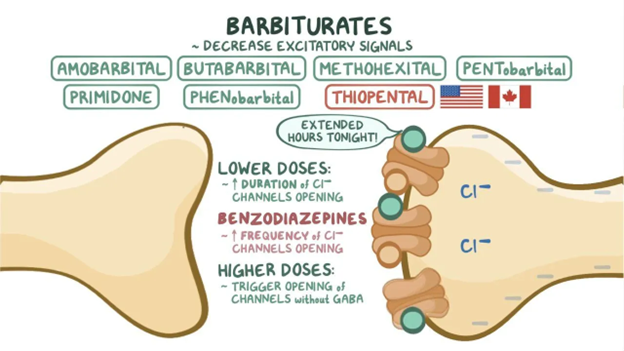

1900s–1950s: Barbiturates Dominate and Reveal Serious Risks

Barbiturates such as phenobarbital and secobarbital quickly became the standard for insomnia treatment. They were powerful and reliable but came with significant dangers: a narrow therapeutic window, high overdose risk, rapid tolerance, severe withdrawal, and deadly interactions with alcohol and opioids. Their widespread use underscored an emerging truth. Effective sedation without safety is not a sustainable long-term solution.

Anticonvulsants and anxiolytics: Barbiturates: Video. Osmosis. https://www.osmosis.org/learn/Anticonvulsants_and_anxiolytics:_Barbiturates

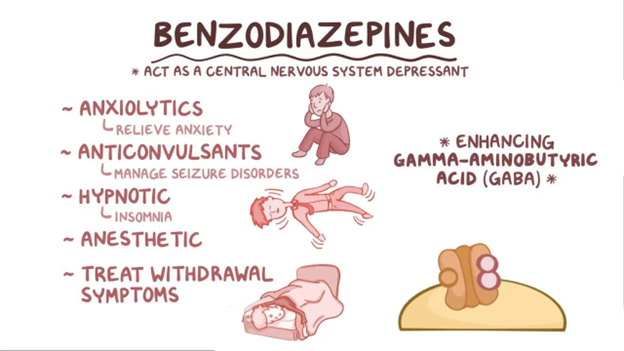

1960s–1980s: Benzodiazepines Offer a Safer Alternative

The introduction of benzodiazepines, starting with chlordiazepoxide (Librium) and diazepam (Valium), marked a turning point. These drugs enhanced GABA-A signaling with far lower overdose risk than barbiturates. Hypnotic benzodiazepines like flurazepam, temazepam, and triazolam became common for insomnia. However, over time, clinicians observed important limitations: tolerance, dependence, cognitive impairment, and rebound insomnia, especially with short-acting agents.

Anticonvulsants and anxiolytics: Benzodiazepines. Osmosis. https://www.osmosis.org/learn/Anticonvulsants_and_anxiolytics:_Benzodiazepines

1990s–2000s: Introduction of Non-Benzodiazepine “Z-Drugs”

Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, including zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone, were developed to act at GABA-A receptors through a different binding profile than traditional benzodiazepines. These agents can improve sleep onset or maintenance depending on the molecule and formulation. However, Z-drugs are known to cause rebound insomnia when discontinued, particularly after higher doses or prolonged use. They also carry a Boxed Warning for complex sleep behaviors such as sleep-walking, sleep-driving, and other activities performed while not fully awake. The FDA later applied warnings about complex sleep behaviors across the broader sedative-hypnotic class after recognizing this adverse effect pattern. Misuse and abuse have also been reported in some populations, underscoring the need for appropriate prescribing and monitoring.

2010s–Present: Therapies Targeting the Orexin Pathway

Advances in sleep-wake neurobiology have contributed to the development of insomnia therapies with different mechanisms of action. One such approach involves Dual Orexin Receptor Antagonists (DORAs), including suvorexant, lemborexant, and daridorexant, which act by blocking wake-promoting orexin signaling. Clinical studies show that DORAs can improve sleep onset and maintenance without producing clinically meaningful rebound insomnia or withdrawal. However, like other Schedule IV hypnotics, they carry the potential for abuse and misuse, and they are associated with specific adverse effects such as sleep paralysis and hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations. DORAs are also contraindicated in patients with narcolepsy, and individual agents may differ in next-day effects; for example, some data suggest daridorexant may have comparatively higher rates of next-day somnolence in certain populations.

Where We Are Today

Current guidelines emphasize Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) as first-line therapy, with medications used selectively and often short-term. Still, pharmacologic sleep aids remain important tools when guided by knowledge of mechanism, safety, and patient-specific factors.

Onward to More Personalized, Physiologic Sleep Therapies

From herbal potions to synthetic sedatives, benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, and orexin antagonists, each era of sleep aids built on and corrected the limitations of the last. Today, progress in circadian biology, pharmacogenomics, and neurophysiology is shaping the next generation of sleep treatments. The future of insomnia therapy will focus increasingly on understanding natural sleep patterns and developing more personalized approaches that support healthy, restorative sleep.

References

- López-Muñoz F, Ucha-Udabe R, Alamo C. The history of barbiturates a century after their clinical introduction. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2005;1(4):329-343.

- Neubauer DN. The evolution and development of insomnia pharmacotherapies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S11-S15.

- Edinoff AN, Wu N, Ghaffar YT, et al. Zolpidem: efficacy and side effects for insomnia. Health Psychol Res. 2021;9(1):24927. doi:10.52965/001c.24927

- Schoedel KA, Sun H, Sellers EM, et al. Assessment of the abuse potential of the orexin receptor antagonist suvorexant compared with zolpidem in a randomized crossover study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(4):314-323. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000516

- Herring WJ, Connor KM, Snyder E, et al. Suvorexant in patients with insomnia: pooled analyses of three-month data from phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trials. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(9):1215-1225. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6116

- Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(2):307-349. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6470

- Hu Z, Oh S, Ha TW, Hong JT, Oh KW. Sleep-aids derived from natural products. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 2018;26(4):343-349. doi:10.4062/biomolther.2018.099

The information provided is for general informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended to serve as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The content is written by a licensed pharmacist and reflects general knowledge and expertise in the healthcare field, but it is not a substitute for professional medical advice from a qualified healthcare provider.

Always consult your physician, pharmacist, or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, stopping, or modifying any medication, treatment, or health regimen. Individual health conditions and needs vary, and only a healthcare professional can provide personalized advice tailored to your specific situation.

While we strive to ensure the accuracy and currency of the information presented, medical knowledge is constantly evolving, and errors or omissions may occur. The blog’s content does not cover all possible uses, precautions, side effects, or interactions of medications or treatments. Reliance on any information provided is solely at your own risk.

Links to external websites or resources are provided for convenience and do not imply endorsement or responsibility for their content.